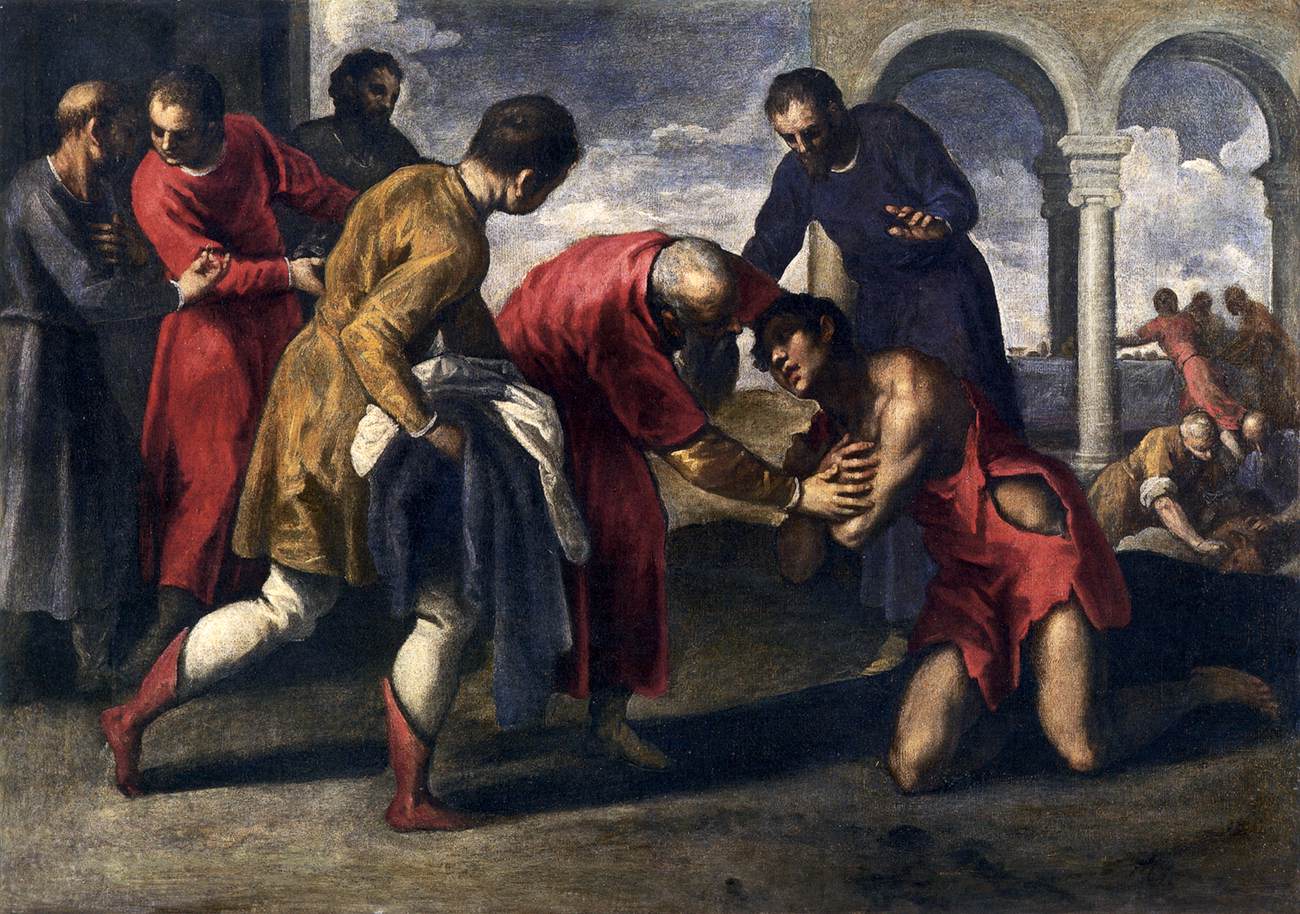

Quizás no hay otra parábola de Jesús más conocida que la que oímos hoy: la parábola del Hijo Pródigo. Pero nombramos mal la parábola, porque el verdadero pródigo es el padre, no el hijo menor.

El diccionario dice que «pródigo» quiere decir «disipador, gastador» o «muy dadivoso.» Es la primera definición que da a la parábola el nombre del «Hijo Pródigo» porque el hijo menor disipó y malgastó la herencia que había recibido de su padre. Pero según el segundo sentido de la palabra—«muy dadivoso»—el padre es el pródigo. ¿Por qué? Porque da generosamente de su amor, su cariño, y su perdón. Hasta da demasiado, según el primer hijo y según costumbres y prácticas tradicionales. ¿Cuál padre, después de que su hijo no podía esperar la muerte de su padre para recibir su herencia, trataría a su hijo como lo trató el padre en la parábola? ¿Cuál padre celebraría la avaricia, la falta de respeto, y la tontería de su hijo con una fiesta? ¡Hasta le devuelve el anillo que significa el poder de las cuentas de la casa!

Nuestro Dios es el «Padre Pródigo.» Nos cuesta entender —como ni el hijo menor ni su hermano mayor podía entender —que el amor de Dios lo conquista todo, aun el pecado y la muerte («Tu hermano estaba muerto y ha vuelto a la vida» [Lucas 15:32]). Somos de «cabeza dura», como dijo Dios a Moisés de su pueblo en la primera lectura [Éxodo 32:9]. Y lo que dijo San Pablo en la segunda lectura de sí mismo podemos decir de nosotros mismos: «Dios tuvo misericordia de mí…y la gracia de nuestro Señor se desbordó sobre mí» [1 Timoteo 1:14]. Que la gracia de Dios «se desbordó» quiere decir que Dios es un «pródigo», que Dios es muy dadivoso.

Con regularidad escucho en mi oficina o en el confesionario a uno que dice, «No sé si Dios me perdonará o no…» Si Dios perdonó a los israelitas su idolatría (primera lectura), y si Dios perdonó a Pablo su blasfemia y su violencia contra la iglesia (segunda lectura), y si Jesús nos narra la parábola del perdón de un padre a un hijo que le había insultado y ofendido tanto (el evangelio), ¿cómo es que creemos que nuestros pecados son tan grandes y tan malos que en nuestro caso Dios ha llegado a su límite y no nos perdonará? Pablo escribió a Timoteo que él (Pablo) era «el primero» de los pecadores, y la gracia de Dios se desbordó sobre él, y escribió en otra carta a los romanos, «donde abundó el pecado, sobreabundó la gracia» [5:20]. ¡Siempre hay más gracia que pecado! Y si vamos a creer lo que Jesús dijo en el evangelio de hoy, ¡a Dios le agrada más el pecador arrepentido que un santo fiel! [Lucas 15:7]. ¡Qué Dios tan pródigo!

–

There may not be another parable of Jesus that is more well-known than the one we hear today: the parable of the Prodigal Son. But we have misnamed the parable, because the truly prodigal one is not the younger son, but his father.

The dictionary defines the word “prodigal” as “exceedingly or recklessly wasteful” and “extremely generous; lavish; extremely abundant.” So, okay, by the first definition of the word the younger son can be said to be prodigal, for he recklessly wasted his inheritance. But by the second definition it is the father who is prodigal. Why? Because he was extremely generous, lavish, and abundant with his love, his affection, and his forgiveness. Even recklessly so, according to the older son, and according to common custom and practice. What father, after his son said he couldn’t wait for him to die before getting his inheritance, would treat his son like the father of the parable did? What father would celebrate the greed, the lack of respect, and the foolishness of such a son with a party? He even gave his son the signet ring that represents power over the money accounts!

Our God is the “Prodigal Father.” We have difficulty believing—as both the younger and the older sons had difficulty believing—that God’s love conquers all things, even sin and death (“Your brother was dead and has come to life again”[Luke 15:32]). We too are a “stiff-necked people,” as God described the Israelites to Moses in the first reading [Exodus 32:9]. And what Saint Paul wrote in the second reading about himself is something we can say about ourselves too: “The grace of the Lord has been abundant” [1 Timothy 1:14]. That God’s grace is “abundant” means that God is “prodigal,” that God is lavish and generous.

With regularity someone in my office or in confession says to me: “I don’t know if God will forgive me…” If God forgave the Israelites their idolatry (first reading), and if God forgave Paul his blasphemy and violence against the church (second reading), and if Jesus tells a parable about a father who forgives such an insulting and disrespectful son (gospel), why do we think that when it comes to our sins God has reached the limit of forgiveness? Paul wrote to Timothy that he (Paul) was the “foremost sinner” and yet God’s grace was abundant toward him, reminding me of what Paul also wrote to the Romans: “Where sin abounds, grace more than abounds” [5:20]. There is always more grace than sin! And if we are going to believe what Jesus said in today’s gospel, then a repentant sinner makes God happier than a faithful saint! [Luke 15:7]. What a prodigal God!